Where is the summer, the eternal, zero summer?

“Little Gidding,” Four Quartets, T.S. Eliot

One morning a few weeks ago, the eastern light cast leaf-shadows on the floor of my room, sharp and clear as a shadow puppet play. The wind was so strong that day that it churned up the leaves and their shadows into a wild dance, graceful and mesmerizing. When I went outside, the rushing wind rustling the leaves sounded like a roaring river: silvery, whispering, rushing, trembling.

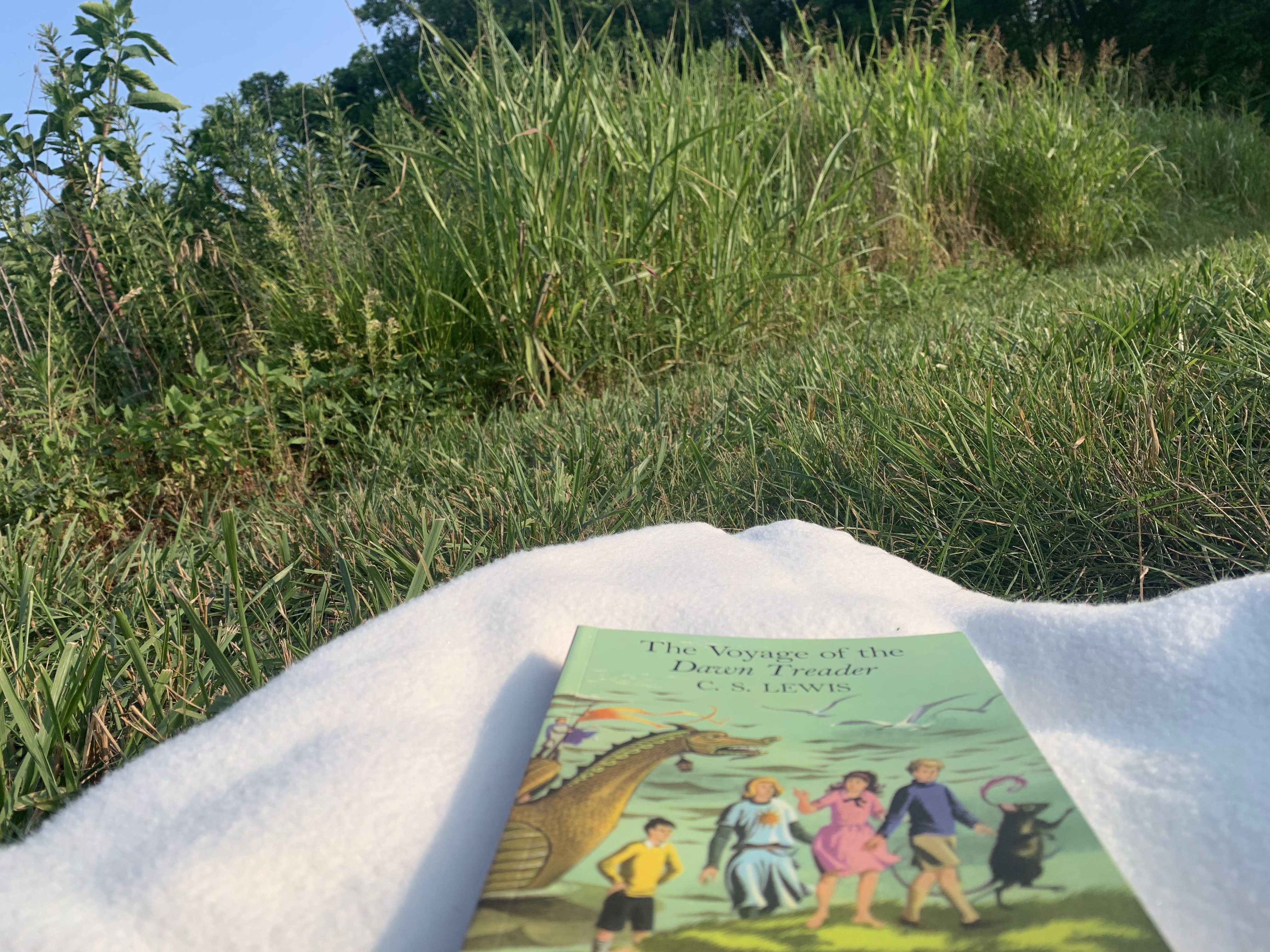

This is my favorite time of year, in close competition with the twinkling merriment of Christmas. Soft green leaves, blossoming peonies, golden buttercups, pert bluets, serene roses, and fiercely purple salvia fill the air with sweetness; picnics, beach days, water sports, and barbecues feel like a proclamation of the goodness of life; humming crickets and cicadas, along with cooing mourning doves in the mourning, make everything feel hazy and lazy, sweet and mysterious. It always feels like a happy ending, or a suspenseful beginning. It’s a time for feasting, playing, resting, adventure, and quiet.

I’m trying to use these dreamy days to rest, resisting the urge to fill up my days with more and more and more – more books, more writing projects, more research investigations, more activities. But I have enjoyed a few projects lately:

The Faerie Queene: Allegory and Adventure

This summer, Dr. Junius Johnson is offering online courses on “Forgotten Epics”: great, influential works that no one reads any more. I took his May-June offering on Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590). Before this course, I’d felt guilty for a long time for not reading this book, after hearing about how it influenced C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, George MacDonald, and countless other writers.

After reading all 30,000 lines of poetry, I don’t feel guilty about how long I waited. It is a hefty tome, and very difficult. Spenser, a contemporary of Shakespeare, wrote this in the 1590s and intentionally used archaic language and inconsistent spellings. He swaps his u’s and v’s, uses forgotten words like “eftsoones” (“soon after or immediately”), occasionally switches speakers without using quotation marks or he said/she said tags, and will deviate from the main storyline to a subplot for a while before returning.

I struggled through the text with help from the footnotes, but for all that, The Faerie Queene is a fascinating, wondrous, wild, fantastic adventure. Books 1-3 and the unfinished fragment of Book 7 were my favorites, full of questing knights, dragons, giants, perilous woods, and mysterious castles and mansions with inhabitants who could be grand and good or wicked and deceptive. Some reflections along the way:

- Allusions — A big part of the fun of the Faerie Queene is spotting characters, settings, and symbols that later authors borrowed. C.S. Lewis drew heavily on this work in The Chronicles of Narnia: for example, Spenser’s Redcross Knight grabs a snake/woman monster by the throat in a fight in Book 1, just as Prince Rilian grabs the serpent in The Silver Chair to slay it. John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, George MacDonald’s Princess books and Phantastes, and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series all draw on Spenser’s symbolism and action in their worlds.

- Allegory — As Junius Johnson discussed in class, people assume they can read any story allegorically, but “pure” allegory — a story in which every character, setting, or object directly represents an abstract idea — is actually very hard to write. Spenser does better with places and monsters than people; his people are just a little too well-developed to represent just one idea. For example, Britomart, the female knight who represents Chastity, is both fierce and tender, an unmatched warrior, and sometimes reckless. She has too many layers to represent just one virtue.

- Mythical houses — As I told some friends along the way, I’m finding that my favorite literary setting are houses full of mythical, fantastic creatures and objects. Some of my favorites in this book were the House of Pride, where the Seven Deadly Sins gather under a sinister queen named Lucifera; the House of Temperance, where three sages of past, present, and future dwell in a tower; the House of Proteus, the shape-shifter of the sea, where all the personified rivers of the world gather for a feast; and the silver palace of Cynthia, in the sphere of the moon. I think these exotic settings satisfy my desire to escape the ordinary details of life that can feel so mundane, like getting gas or paying bills, and remind me that the real world is full of wonders.

- Pageants — Apparently, pageants were very popular in Renaissance/medieval times. There are plenty of pageants in the FQ: a pageant of the Seven Deadly Sins in the House of Pride in Book 1, and a pageant of the consequences of unchaste love in Book 3. The color, splendor, and symbolism of these scenes caught my imagination.

The Faerie Queene is a book best tackled one piece at a time, with a group — I don’t think I would have had the persistence to finish it alone! It deserves an even deeper study than I gave it this time, but this was a good introduction to the foundations of fantasy.

The Book of Joel: Repentance Brings Restoration

This summer, I’m doing a study of the Biblical book of Joel. I chose it because I’ve never studied it before, I like how shorter books of Scripture allow you to see the author’s structure more easily, and I want to keep practicing Bible teaching. I knew about the Pentecost prophecy in chapter 2 (“I will pour out my Spirit on all people,” fulfilled in Acts 2) and Bible Study Fellowship touched on it briefly in their overview of the Old Testament, but other than that, I knew very little about it.

If Dante had not already used the title for his masterwork, Joel could be called “a divine comedy” – it feels like a short play that goes from dread and doom, to hope, to a happy ending. In some ways, the book is a microcosm of the whole Old Testament and the Bible — a disaster invited by disobedience, warnings of dread and doom and darkness, a call to repentance, a vision of judgment, and a beautiful promise of restoration. It’s full of rich images like a plague of locusts, the vine and the fig tree in the Promised Land, the day of the LORD, a resurrection of land and hearts, and Mount Zion, the city of God. Like Isaiah and Jeremiah, it includes fearsome warnings and compassionate invitation, images of destruction and recreation.

The heart of the book, structurally and interpretively, is Return to me: return to the LORD in repentance to receive restoration, revival, and resurrection. Reading it reminds me that the LORD desires my heart, and not just my habits and actions. Also, He calls for obedience so that He can bless us.

Artificial Intelligence: Reckoning with the Next Tech Revolution

While my free time is full of adventure stories and prophecy, I’ve also been contemplating a third topic from my work life: AI. Generative AI and agentic AI are nothing new; not for decades, and not since the release of ChatGPT in 2022. But they didn’t become real to me until about a month ago, when I began encountering them more frequently.

As a believer, English major, storyteller, and wordsmith, GenAI and agentic AI have me worried. Like many people, I fear for my job – machines that can create messaging and content could replace me. But they also make me fear for our culture.

Here are some reasons why I want to be cautious with AI:

1. Critical thinking is a gift

Critical thinking tasks like writing are good for you, just as much as running, swimming, and dancing are good for your mind and body. Staring at a blank page, trying to frame a sentence, spark an idea, structure an article, or select the right word is a mental labor that we shouldn’t try to skip. I listened to Nicholas Carr’s The Glass Cage recently (a book on automation published in 2015, so not about GenAI, but definitely applicable). Carr discusses how automation encourages the human supervisor to “tune out,” disengage, and lose their ability to react quickly when needed. He calls it “automation complacency.” Removing effort and concentration from a task take the pleasure away from the human operator — and can introduce new risks if something goes wrong that automation is not programmed to handle. I recommend Carr’s book as a great resource for thinking about a human-centered approach to technology.

Advocates of GenAI keep repeating the benefits: it will save time and energy, so that you can do more and work faster. But if using GenAI costs you mental agility, energy, and the sheer pleasure of good work, is that exchange worthwhile? How can you make sure it doesn’t leave you sluggish, permanently tuned-out, unable to focus, and powerless to decide on your own?

I know and work with some brilliant people who are using GenAI as a tool, not as a replacement for thought. These people use sophisticated prompt engineering to train their chosen AI platforms to write more clearly, avoid repetition, research thoughtfully, and use trusted sources. They review the AI output and have the expertise to measure its accuracy; they hone and refine word choice and analogy to remove the robotic tone and make it their own. What worries me are people who seem to think that AI removes their need to think at all. I’ve received clumsy, inaccurate GenAI outputs from people who didn’t read what they sent before they sent it. Agentic AI can prioritize your tasks, write your emails, gather your research, answer your questions, and even look at a photo of your fridge and tell you what to make for dinner (someone actually told me that’s how they use it). But how can you be sure the decisions an AI agent made for you are good ones, especially if you’re not keeping your own decision-making skills sharp through practice?

2. Words are relational

GenAI can multiply your content output exponentially. It could allow you to produce dozens, hundreds, or thousands more articles, essays, books, and other content than you could with pen and paper. I could have produced hundreds of blog posts in the time it’s taken to write this one on my own. But more is not necessarily better, especially when it comes to content.

Content is relational. In business, content conveys a company’s brand voice to its customers, prospects, and partners. You’re persuading, communicating, teaching, and asking. Assigning that relational work to a machine means that you have less control over voice and tone – or, on the other side, less ability to be original, since AI can create anything new. Choosing the right word for the audience, situation, and task at hand is taxing work, but worth the time and energy it takes. Saying that something is “ancient” vs. “old,” “innovative” vs. “creative,” “disastrous” vs. “troubling” is a choice that requires the author to understand the cultural meanings, historical layers, nuanced definitions, metaphors, and assumptions at play between herself and her reader.

3. Research is a gift

Research is another area I worry about. In business, research is utilitarian; you only look up as many sources as you have to before using it to create content or make a decision. But in general, research is “inefficient” because it’s shaping the heart and mind of the researcher as well as getting them to their stated goal.

In academia, the long, hard slog of research is what makes a PhD student into a well-rounded scholar in their subject area. Their dissertation is only one facet of that degree; the real work is reading books that you may not even use, listening to all the voices of the past and present, and responding to them with your unique perspective. When I wrote a paper on L.M. Montgomery, I read many journal articles, books, and dissertations I never cited — but they gave me a wealth of knowledge about topics like Scottish Presbyterianism, life-writing, William Wordsworth, Percy Bysshe Shelley, the imagination, and Prince Edward Island.

Using GenAI to shortcut the journey of the research process robs you of the person you could become if you read books, articles, essays, or studies in full and stored up that knowledge, making your mind into a living library that can grow new insights and connections. (I recommend another book by Nicholas Carr, The Shallows, on this topic – he examines how organic memory is superior to digital memory because knowledge grows in your mind instead of staying static.)

4. Words shape reality

When I was in grad school, we had a seminar series on “Metaphysics and Poetics” with the Cambridge Dean Society. Most of it was sky-high over my head, starting with the title, which can be translated as “The Relationship Between Language and Reality.” How do the words we use shape our perception? When we name or describe something, are we recognizing its qualities or defining them?

Words reflect and shape reality because reality came from words: the Word, Jesus Christ, the Son of God. In my book of John class in undergrad, we spent a whole week on the glorious opening to the book: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made.” (John 1:1-3)

I don’t have the time here to explore all the Scripture passages about words: the book of Proverbs has some clear guidance (Proverbs 10:20, 12:19, and 15:4, for instance); James warnings about the power of the tongue (James 2); names, stories, laws, blessings, curses, lies, wisdom, folly, and direct revelation are constructed with language. Words shape perception and opinion; they can give life or cause death. Using GenAI to generate text gives it authority to shape our thoughts, and thus our behavior and decisions. Is this worth it? How can we make sure that our GenAI models, or the people who built them, are not subtly manipulating our thoughts? And do you want to put your name on words that a machine generated?

Final Thoughts

I can’t change how other people use AI, and I do need to explore ways to use it ethically, creatively, and thoughtfully. That means investigating which problems AI can solve, training myself to build AI agents, and learning which models are good for which types of work. But I don’t want to become numb to the ways it can shape my thoughts and decisions. I also think there will be a backlash at some point: culturally, legally, or even logistically (AI violates the spirit of copyright laws, if not the letter, and it takes a lot of compute power).

In a digital world, it’s easy to fall into the trap of faster-faster-faster, more-more-more. Human beings were not meant to live and consume at an increasingly accelerated rate. I’m recognizing my need to slow down, rest, and savor one good thing at a time instead of multi-tasking. I guess that’s part of the feast of summer: enjoying things with an abundance mindset, trusting the Lord that there will be enough.