I finally got to travel. After yearning for it in the golden fall, dreaming of it in the windy winter, and planning for it in the cool green spring, I finally got out to the Highlands & Islands and a bit of the Lowlands: the Isles of Mull, Staffa, and Iona one weekend, the Isle of Skye, and then Edinburgh.

It’s been glorious, exhausting, enlightening, stressful, blissful. Hikes across emerald slopes sprinkled with tiny daisies, buttercups, purple heather, and fluffy cotton-grass; cozy evenings in wood-paneled pubs with tartan carpeting and paintings of antlered deer; ferry rides past rugged peaks and lonely islands; views of faraway blue hills and glimmering lochs; laughter and long talks on train and bus rides.

Each place gave me memories, dreams, and fragments of stories.

Iona

Sacred Haven

Iona is a tiny island, 3 square miles, with only 150 permanent residents and herds of grazing sheep and Highland cows (“coos”). It is also the place where St. Columba landed from Ireland in the 500s (1500 years ago!) and started an abbey. A replica/rebuild of the abbey is there today, full of the remnants of Celtic crosses, new sandstone pillars covered in intricate carvings, and ancient gravestones.

One of my favorite insights was seeing the snake-and-boss design. Despite the Edenic tradition of snakes as creatures of evil, apparently the medieval Christians saw the casting and regrowing of skin as a symbol of death and resurrection. I have heard whispers of the richness of Celtic Christinaity, of thin places and rhythms of life and mysteries incarnate in the natural world (such as clovers representing the Trinity) but I want to study more. The whole island felt quiet and sacred – a place to come and heal, walk the pasturelands and talk to God, and feel connected with the great cloud of witnesses that is the universal Church.

Story fragments

- A sacred place of healing

- An island at the end of the world

- An abbey with a buried treasure

Staffa

Lonely Marvels

Staffa is even tinier than Iona, shaped by some geological process I still don’t fully understand to have natural hexagonal pillars. It looks giant-carved. We rode out by ferry for an hour, chilled by the sea-wind and enchanted with a fluffy white dog who loved us dearly, and then had an hour to explore it. We sprinted down to the wonder of Fingal’s Cave, aquamarine water in a deep black vault, and then back across the steep cliffs to see the PUFFINS. They were just as clownish and cute as we hoped, though tinier. They didn’t care anything about us, but launched off into the sky as a dark seabird flew overhead.

Story fragments

- People resettling uninhabited isles and encountering magical creatures

- An echoing cave that is really a shadow kingdom

- A tour boat crew that has a special understanding with the mermaids in the area

Skye

Blue Kingdom

Skye is more rugged than Iona, Mull, or Staffa. It’s also many shades of green and blue, with steep cliffs, purple heather, gray rock, and the same sprinkling of wildflowers. Slender waterfalls wend their way down the hills, among the evergreens. A Scottish shepherd recommended a gorgeous hike across the cliffs that gave us exquisite views: distant azure mountains, white sailboats on the sea, and window panes glittering in the town. We couldn’t capture it in photos, though we tried very, very hard. The shepherd also told us about the Nicholson clan of Portree (Port Righ in the Gaelic) who went broke in the 1800s and emigrated to Tasmania and the Carolinas.

We spent Sunday afternoon with Skye’s Magical Tours: an ex-fisherman named Brian took us to the glimmering Fairy Pools and around the island. Skye was magnificent, so old and huge that I felt small and lonely. We filled it with laughter, with dinner of shepherd’s pie and philosophical discussion, mornings of berry-and-Nutella crepes and foamy cappuccinos.

Story fragments

- Cloud-creatures in a mountain country

- Fairy folk who are defined by the color blue (as opposed to green, the traditional elvish color in Scottish lore)

- Visitors arriving at a shepherd’s cottage

- Selkies at twilight

Edinburgh

City of Stone

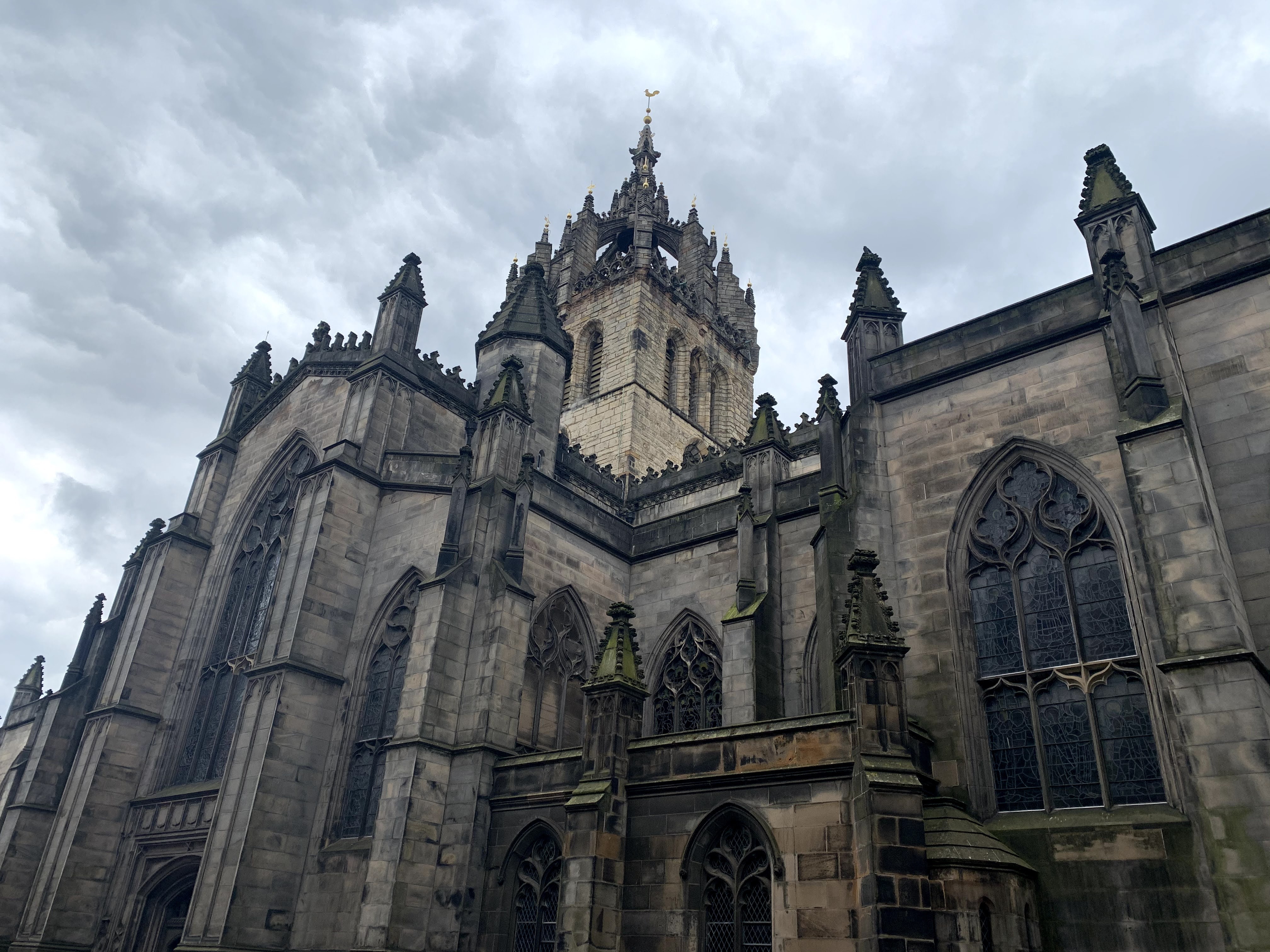

After several trips in the wild, it felt strange to be in a busy city: buses and trams on Princes Street, women in flowery dresses, shops with tartan scarves and Celtic jewelry, gardens of pink roses and fragrant honeysuckle, Gothic architecture, and modern tinted windows. We feasted on the best of Edinburgh: touring the gilded halls of Holyrood Palace, cullen skink and clotted cream raspberry cheesecake at a cozy pub, dizzying views from Arthur’s Seat, dappled sunlight on the river by St. Bernard’s Well, and golden hour in Greyfriars Kirkyard.

Story fragments

- A tiled fireplace with a secret message (I fell in love with Holyrood Palace’s tiled fireplaces)

- Swans and a ruined abbey

- Queen Ann’s lace on a dormant volcano

- A locked well with healing powers

- A brownie who lives at an Air BnB

Meditation: Commercialization vs. Reenchantment

In Edinburgh, thoughts planted on Mull, Iona, Staffa, and Skye finally took root and began to sprout: I realized how dramatic the tourism industry is in Scotland, and probably in other places. I mean “dramatic” in the sense of performative or theatrical: the little shops in Iona, Portree, Old Town, and other places shout all the most distinctive and unique aspects of Scottish culture and history to attract attention. The symbols of Scotland’s Scottishness – tartan, bagpipes, highland cows, the Loch Ness monster, Celtic runes and symbolism, ancient ruins, haggis, thistles, unicorns, and teapots – are the most prominently displayed where strangers and foreigners like me can purchase them and carry them home, like chipping stones from a crumbling castle. Scottish people cannot love tartan that much; it’s outsiders who want the flavor and breath and music of Scotland, because we want to come and experience something fresh and different and fully its own, individual self, somewhere unlike our home place. Most Scottish people shop at the T.K. Maxx or luxury mall we visited, which are almost identical to retail in America.

That made me sad. I know the Western world has many similarities – celebrities are popular in multiple countries, and so on – but I would hate to have all the beautiful distinctiveness of Scottish lore and heritage as a thing of the past. I have only been a Master’s student in an international university town for a year here, so I don’t feel that I really know the Scottish people and culture. But the sheer clamour of a few shops in New Town in Edinburgh made me uneasy, as if only the tourist industry wants to preserve full and distinctive Scottishness – and then, only to sell it.

But I have tasted Scottish culture in literature. I’ve been a dragonfly skimming the depths of it: Scottish fairy tales like “The Well at the World’s End” and “The Black Bull of Norroway,” ballads like “Tam Lin” and “Thomas the Rhymer,” the mesmerizing fantasies of George MacDonald, the Jane Austen-ish societal explorations of Margaret Oliphaunt, the exquisite prose of George Mackay Brown, the haunting tales of James Hogg, and the simple profundity of Alexander McCall Smith. My side-project next year will be to delve more deeply into these and more.

These writers imbibed Scottish tradition and added to it, weaving the desires, dreams, fears, and tensions of their own time into the loom of myth and legend. As I writer, I want to follow in their footsteps and tell stories that help reenchant places like this. I want to reawaken the wonder of selkies on the beach in the moonlight and fairy folk dancing under the green hills, as well as capturing the mystery and dangers of our own time: the whispered rumors and masked faces of COVID, the political tensions that are re-tribalizing countries and regions, the seductive illusions of social media, and the now-too-familiar marvels of the Internet and smartphones.

St. Andrews

Gray Havens

After so many buses, trains, and ferries, it is good to be in St. Andrews again. I’m astonished to find that after magnificent peaks and staggering views on Skye and Arthur’s Seat, the soft, golden-green beauty of fields and woods heals me instead of overwhelming me.

This place is not home. It’s only mine for the rest of the summer. But I will love every day I have left.