After some amazing contributions to the Summer of Faerie project by AJ Vanderhorst, Matthew Cyr, Loren Warnemuende, Rachel Donahue, Emma Fox, Rachel Greco, and William Stark, here is my own Faerie story for the summer. I wanted to do a retelling of one of my favorite tales – “The Twelve Dancing Princesses” or “East of the Sun, West of the Moon” – but a different, darker story called out to me this time.

I first read about the “Two Sisters” or “Cruel Sister” ballad in Patricia Wrede’s Book of Enchantments; she did a retelling with her own spin on it, so my story is as much a retelling of hers as it is of the original tale. It’s actually a troubling, gruesome story, technically a cautionary tale instead of a fairy tale (according to Angelina Stanford, fairy tales have happy endings by definition), but I felt drawn to it by fascinated horror, sadness, and a desire to reshape it. You can read about the ballad itself and its many versions in this article. I used this version of the ballad sung by Peggy Seeger. I also threw in some research about Scottish Fae and superstitions.

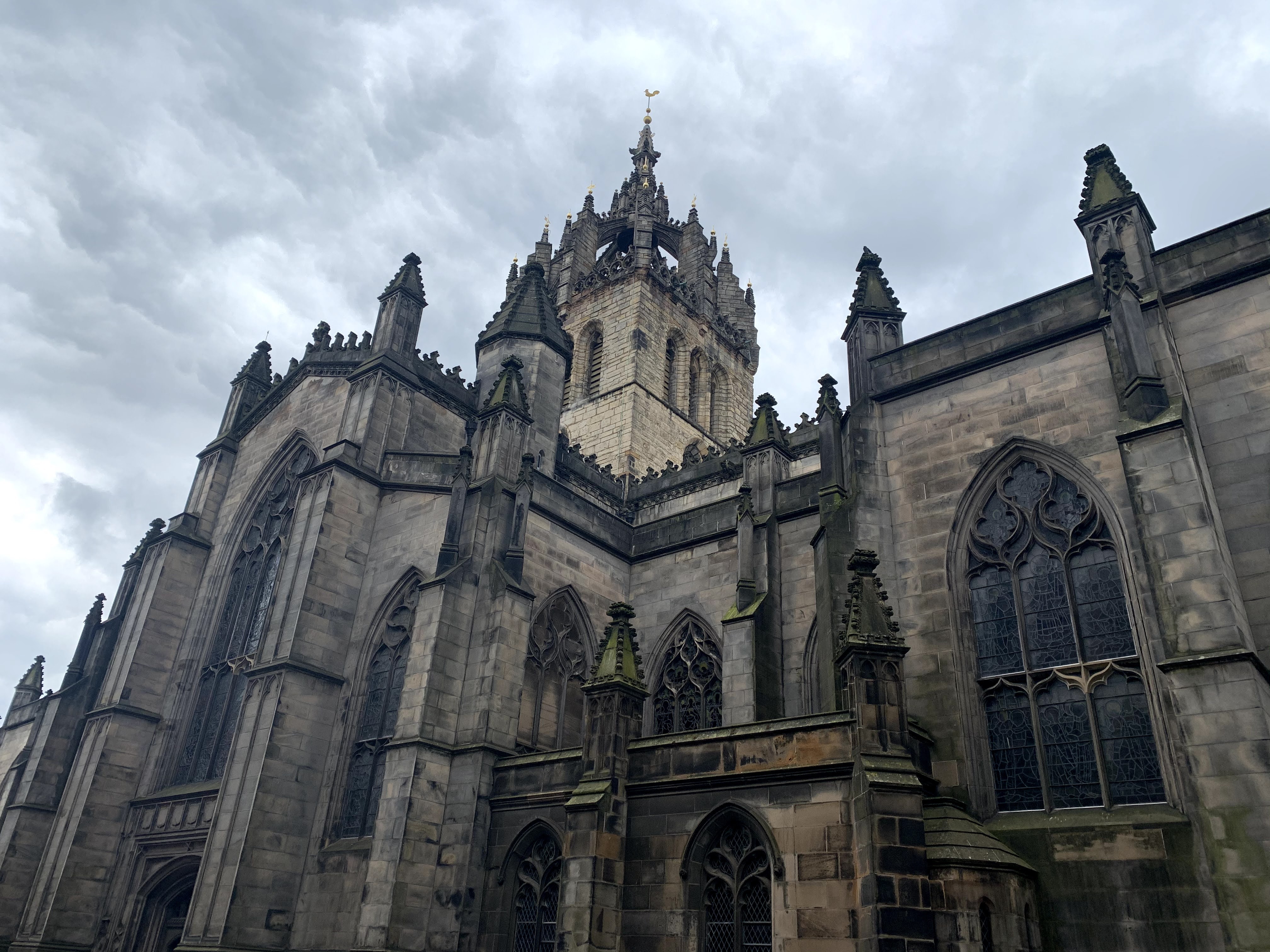

Along with this tale, I have Scottish news. After about five years of waiting, praying, planning, scheming, saving, and doing a lot of paperwork, I’m going to St. Andrews University in Scotland to study for a Master’s degree in Theology and the Arts. The program will let me explore the curious, wondrous region between faith and human creation: how does theology relate to art, and art to theology? How do artists-who-are-Christians integrate what they believe with what they create?

Most of my applications went to literature programs, and I was torn between this degree and one that focused more on the English-major topics I love. I meditated on the decision one bright, chilly morning in April, sitting on the black, red, blue, and gold rug in our front hall and petting our golden retriever as the sun streamed in. The choice came with a surge of joy: I felt that this program would best equip me to use my gifts for the Kingdom of God, to figure out how my writing can be an act of worship.

I have dreamed of going to grad school to study further since college and through various office jobs in a green farm town, silver seaport, and tinted-glass greenhouse. In those years of waiting, I often let myself sink into social media envy (a cliche of our age, I know): envying Facebook friends and Instagram profiles for their exotic vacations, gorgeous weddings, or grad school achievements. Now that I have a life event that looks good on social media, I feel shy.

This coming year is a divine gift, splendidly undeserved. It’s also the product of some hard and unglamorous work, like long periods of loneliness, bumbling through grad school research and applications, international wire transfers, and visa paperwork. Becoming a grad student is a fairy tale written just as much with stress and effort as beauty and adventure. And I’m so, so thankful for it.

Anyway, here’s my story. Enjoy!

True to Me

Our backyard was dim with dusk. The harbor’s salty breeze mingled with the smell of scallops and haddock grilling on the patio.

My older sister Eara’s navy dress smelled faintly musty after 11 months in her closet. It fluttered around me as I rushed down the stairs to the rehearsal dinner laid out on the patio, carrying a flat package.

My oldest sister, Aileen, sat with her fiancé, Mike, a tall man with dark brown skin, broad shoulders, and gold-rimmed glasses. Aileen leaned forward to let him whisper something in her ear. A wave of her dark hair fell onto the shoulder of her green dress. Her expression relaxed into a quick smile before resuming its concentration.

Don’t forget to smile, I remember Eara telling Aileen years ago, before Aileen’s first violin recital. Your concentrating face is kind of scary.

My nervous smile is scarier, Aileen had said.

I looked up at the trees; my little cousins, the other bridesmaids, and I had had a hard scramble to string the golden fairy lights up there, but the looping pattern matched my concept sketches exactly. They completed the atmosphere I wanted: warm, bright, and safe.

You’re quite the Maid of Honor, my mom had said when we finished the lights.

Eara would have been chill about it, I said. But at least I can make things look nice.

Turning to the gift table, I put my package with the other presents: a watercolor painting I’d done of a sailboat on this very harbor, with the land in turquoise and the sail a vibrant orange.

My temples ached with exhaustion; I hadn’t slept through the night in months. Dreams of the pale sun glimmering from underwater and golden hair rippling in a current interrupted my sleep. In waking hours, I kept seeing weird images flicker across peoples’ faces and in their eyes, like shadows or prism-cast rainbows.

Jack, Mike’s younger brother, sat under the maple tree with his guitar. He was leaner than his brother. His skin was a shade lighter and had golden undertones while Mike’s were amber. I squinted: his guitar looked…white? Pale and yellowed, like the whale bones hanging in the Nantucket High School.

I collect instruments that carry stories, Jack told me when I saw him at Easter. He’d showed me his favorite, a guitar his grandfather bought in Berlin in August 1961.

Jack cleared his throat. Our gazes met, and I smiled. He lifted his head slightly in acknowledgement. “I found this guitar on the beach last week,” he said. “And this song kind of wrote itself.”

He began strumming, and in that moment, the instrument in its hand shimmered like a mirage of water – and golden eye in it winked at me. I looked around, but no one else seemed to notice.

I’ll be true to my love, if my love will be true to me, Jack sang with his amber river-voice.

While these two sisters were walking the shore,

Bow, balance to me,

While these two sisters were walking the shore,

The oldest pushed the younger o’er,

And I’ll be true to my love, if my love’ll be true to me.

Audience members looked at each other. Whispers began like a breeze rustling leaves. “Kind of creepy,” my grandmother whispered loudly.

Then, Jack lifted his hand from the instrument, stopped singing, and stared at Aileen. The guitar continued to play on its own. Another voice, my older sister Eara’s summery tones continued:

While we two sisters were walking the shore,

We, Aileen and me,

While we two sisters were walking the shore,

Aileen pushed me into the wat’r,

And I’ll be true to my love, if my love’ll be true to me.

Oh sister, oh sister, please lend me your hand,

Bow, balance to me,

I never, I never will lend you my hand…

Gasps; heads turned to the wedding party’s table. Aileen and Mike exchanged glances, then stood, their chair legs scraping the stone, and ran around the table to Jack. Aileen grabbed the guitar, and they disappeared into the garden.

I was the still point of a turning world. Relatives and friends turned to me, their eyes wide. Last September’s memories rushed through me: the Coast Guard report, Aileen’s days in the hospital, the empty coffin. I walked to Jack, my high heels wobbling.

“Jack,” I said quietly. “What the heck?”

He met my eyes. “I’m sorry,” he said. “They had to know.” Studying his dark irises, I saw swirling mist instead of the long golden shore I glimpsed in there the last time we spoke.

“You’re confused,” I said. “Ok. Stay here. Tell everyone else to stay here and finish dinner.”

“Ok,” he said. I walked into the garden.

Last July, Eara had brought some grad school friends here for the weekend. I came back from my day camp job one afternoon to find them walking back from the beach, sandy and sun-kissed. As I closed my car door, I saw Eara drop her blue towel. One of the guys picked it up and put it around her shoulders. She laughed, flicking a strand of wet blond hair out of her eyes. I saw Aileen at the back of the group, looking at them. The guy was Mike.

Thick cedars screened the garden from the house. Lights glimmered on the harbor’s dark water. Mike and Aileen were in the white gazebo.

“Ow! Bracelet,” Mike grunted.

I walked to the entrance of the gazebo to see Mike hanging onto the neck of a black horse – snap – a black goat – snap – a black rabbit with golden eyes. He managed to keep his grip around the thing’s neck, hanging on as if trying to tame a wild bull with his bare hands. As the rabbit appeared, Aileen snapped her silver bracelet around its neck. It squeaked and lay still. Panting, Mike sat down with a huff, and she sat beside him, holding it in her lap.

Aileen saw me. “Mairi,” she said.

“Ai,” I said, my old nickname for her. My lungs felt small. “Why did that thing say you killed Eara?”

Aileen looked up at me, her freckles standing out more than usual. “It’s, uh…it’s hard to explain.” She looked down at the rabbit, then back at me. “Do you really think I would do that, Mair?”

I studied her eyes: hazel, with flecks of gold. A dappled light like the sun shining through green leaves shimmered over her face – no mist, no darkness, only green and gold.

“No, you wouldn’t do that,” I said. “But what really happened?”

Aileen tilted her head, studying me. “This is a púca,” she said, gesturing at the rabbit in her hands. “It stole Eara’s voice.”

“A shape-shifter?” I said, bending over to look at the rabbit. It panted, meeting my eyes with that gleeful golden stare. “Why would it steal her voice? She’s dead.”

“No,” said Aileen. “She was taken by the Fae.”

When you jump into deep water, you create a thousand tiny bubbles that hover and pop around you. I felt that plunge and tingling sensation now.

“Eara and I were researching the Fae in grad school,” said Mike. “Faerie is drifting towards us again, close enough to visit. She took something they wanted – we don’t know what. Sea Fae took her.”

“We’ve been searching for her all year,” said Ai. “We thought she was in the Aegean, so we booked our honeymoon there. But púcas are Scottish. This is from the Unseelie Court. So she might be there.”

“You knew all year that Eara wasn’t dead, and you didn’t tell us?” I asked. “Ai, seriously?”

“I know. I’m so sorry,” said Aileen. “We weren’t sure anyone would believe us, and telling stories about the Fae attracts their attention. Mike found a safe way to tell me everything after it happened. We…pretended to be dating at first when we were hunting for her, and then we ended up actually wanting to get married. And the wedding was a good cover for quest prep.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I asked.

“You were in Florida,” said Mike. “Sea serpent country. They’re vicious. All Fae can be, really. And capricious, like this púca. It must have convinced Jack it really was Eara’s bones. I need to talk to him.“

“It means we have to act now,” said Aileen. “Before the wedding. Tonight.”

“Yeah,“ I said. “You two get your marriage license and go to the Aegean. I’ll go to Scotland.”

“Mairi, no,” said Aileen. “You don’t know the Fae.”

“I’m the third daughter,” I said. “You don’t think that matters on a quest? Or the ocean dreams I’ve been having about her?”

We stared at each other. “Second sight,” Mike murmured. Aileen mmmed in agreement.

Another strange feeling came to me: I felt that there were four of us standing here instead of three, and tasted snow.

“We‘ll find her,” I said. “Before the winter solstice.”

My gaze drifted to the harbor, into the waiting dark. A cool breeze brought me a hint of music, like a summons.