This winter was full of wonders: long, dark nights lit by Orion and the rest of the heavenly host around a silver moon; days of cold so bitter it felt like my finger bones were freezing; deep snow that froze into crunchy drifts; cancelled church services; drives in the snow; a vigil that ended in a beloved family member sailing to heaven. The days have rushed by like pine trees seen through the window of a moving train, a blur of living, changing detail.

I’ve wanted to update this blog for a while, but I promised myself when I started blog-writing in 2017 that I would only post if I had something worthwhile to offer to readers. Here’s an attempt at an offering: a look at some new books I’ve found, workshops and courses I’ve enjoyed, and a question that’s been burning in me for months.

New Books to Treasure

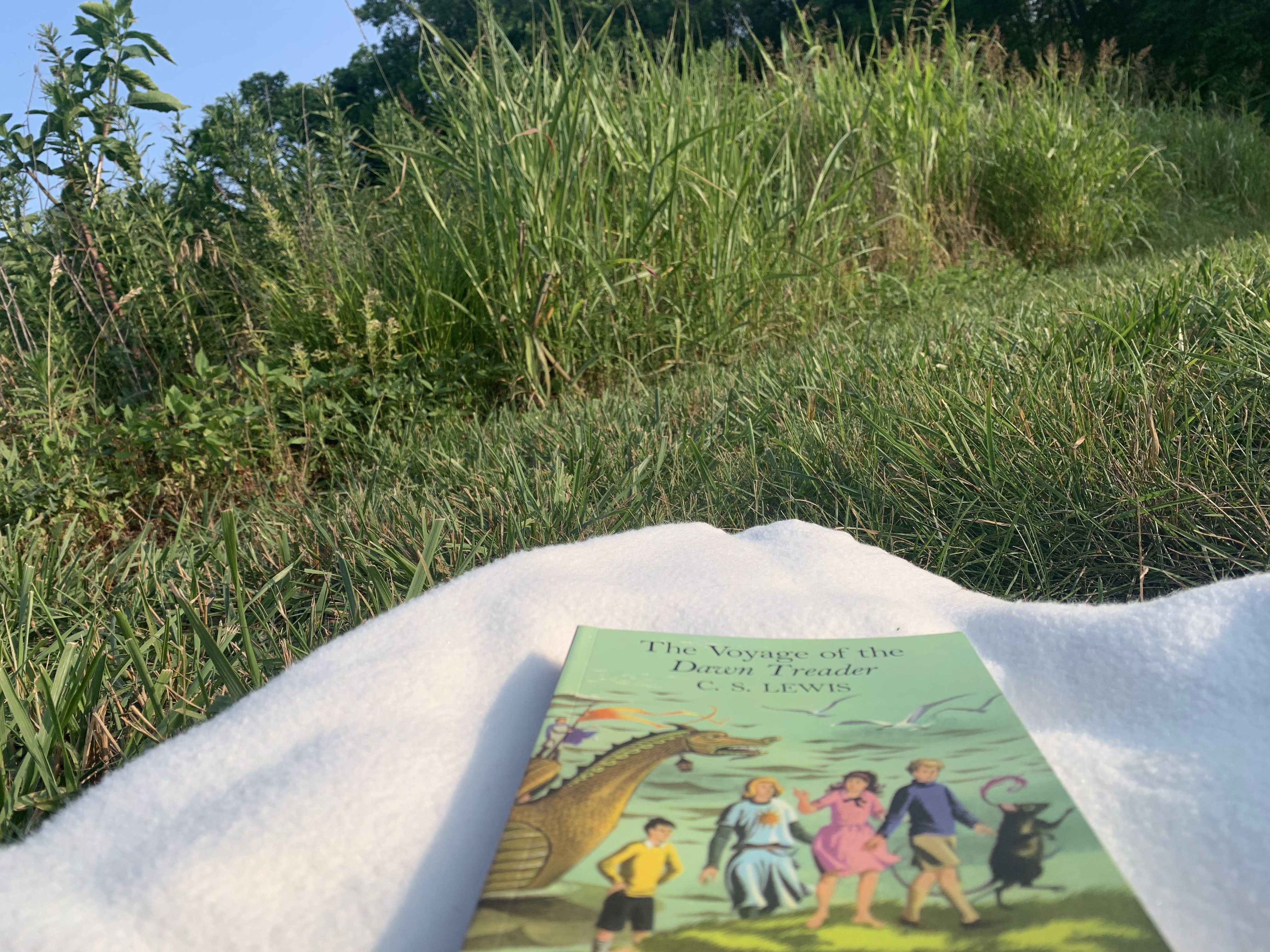

For the last 12 months, I’ve struggled to find good new books, but a few treasures stand out:

- Christina Baehr’s Secrets of Ormdale series — A brand-new, five-book series set in late Victorian England — with an actually likable Christian heroine and dragons? I was so afraid to have hope for this series, but it was marvelous. Christian Bhaer knows her stuff: Scripture, lore, historical and cultural detail history, Anglo-Saxon poetry, literature, and the best slow-burn romance I’ve read in a while are shining threads in this series’s fantastic tapestry.

- J.A. Myrhe’s Rwendigo Tales — Set in central Africa, these books tell the story of four physical and spiritual quests with beautiful prose, exciting drama, and deeply relatable characters. The thoughtful, image-rich, matter-of-fact style reminds me of Alan Patton’s Cry the Beloved Country; the mythical and spiritual elements remind me of C.S. Lewis’s Cosmic Trilogy.

- Diana Glyer’s The Company They Keep — I’ve been meaning to read this one for ages. In beautiful language and lots of deep research, Glyer studies that group of rare imaginations that included C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. She argues that, contrary to what most scholars have argued over the decades, the Inklings did influence each other by resonating, opposing, editing, collaborating, and referring to each other in their creative works. Highly recommended for Inklings fans and artists who long for community.

- James M. Hamilton Jr.’s Typology-Understanding the Bible’s Promise-Shaped Patterns: How Old Testament Expectations are Fulfilled in Christ — I picked this book up on Audible after searching for books on typology, a topic I’ve been curious about for a while. I loved it. It offers a clear and careful examination of the images and structures that Biblical authors use to point to Christ as the king, suffering servant, redeemer of captives, and divine bridegroom. It’s accessible for both scholars and laypeople; joyfully and reverently written; full of brilliant insights about the patterns of Scripture. My favorite takeaway is Hamilton’s argument that the types of Scripture are 1) definitely intended by each Biblical author (not an accident or readers’ construction); and 2) historically grounded (more than just artistic collaboration by the authors).

Beowulf, the Anglo-Saxons, and Learning to Love Something

I began this year with something appropriately wintry and mysterious: a “How to Read Beowulf” course from the House of Humane letters. I’m more of a fairy tale, roses-and-summer reader than a fan of the grim, otherworldy, silvery beauty of Anglo-Saxon literature, but I know C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien loved those tales, so I wanted to see what they saw.

The course was profound and thought-provoking in ways I didn’t expect. Angelina Stanford dived into:

- The ruinous, twilight atmosphere of the Anglo-Saxon period

- The violence of a culture that knew only revenge-killings and ransoms as means of justice

- The nature of the monsters depicted

- The very meaning and value of words

While I’m not sure I agree with every point made, the course left me with much to ponder and an ache to know more. I found myself going back to the very foundations of what a story is, how to read, and how to interpret literature – digging up my Literary Criticism and Theory notes from college, listening to more lectures on the Anglo-Saxon period, and wishing I had Tolkien’s gift for language. I’m newly convinced how much words matter, how every word and name is a story, and how Christ is the sun of righteousness who ends our dark night.

Habakkuk: The Word from the Watchtower

In February, I had the honor of going to a Charles Simeon Trust women’s workshop in Cambridge, MA. The Charles Simeon Trust Society trains Bible preachers and teachers in deep, thoughtful exegesis, theological reflection, and application. This workshop for women was as academically rigorous as any graduate seminar I experienced while also warmly encouraging. This workshop focused on practicing teaching prophetic literature with the book of Habakkuk.

Habakkuk is hard. The Charles Simeon Trust method begins with establishing the context and structure of a particular passage, and Habakkuk’s flow of thought is initially confusing. But it’s beautiful. Habakkuk’s earnest cry to the Lord, and the Lord’s sovereign and gracious response, are deeply comforting. The hymn of praise at the end is one I chose as an anthem for the past years, a song for troubled times.

This workshop showed me how clear, simple, and clean good Bible teaching should be. In my few attempts at teaching, I’ve often tried to dump all my insights, observations, musings, meditations, questions, and research on my poor helpless audience. Instead, the workshop taught me to distill my work into a simple main point that people will remember. For example, my original main point for a practice session on Habakkuk 3:1-19 was Christ is coming to administer justice and rescue His people, no matter how barren circumstances become. After workshopping this part of my presentation with my small group, I managed to streamline it down to Rejoice in Christ’s coming rescue even in barren times — turning an overflowing sentence into a comforting exhortation.

“Writing with The Horse and His Boy”: Rediscovering Old Loves

Yes, my life is merely a progression from one online literary course to another. This one was particularly fun because it was run by Jonathan Rogers, my writing teacher and the proprietor of the Habit writing community, which has been a source of delight, fellowship, encouragement, thought-provoking discussion, and community.

My creative inspiration, which has been fairly dry since January 2023, started to run again in a few of the writing exercises we did together. I remembered how much I love The Horse and His Boy: the beautiful, crisp, clear settings, Shasta’s intensely relatable awkwardness, self-pity, and courage; Bree’s pompous dignity; Aravis’s pride and honor; and the hilarious addresses to the reader. I was newly encouraged to follow tried-and-true writing wisdom like:

- Look through your characters’ eyes and develop them from the inside, by what they notice and how they react

- Stick with concrete details

- Remember that each conversation has layers of dialogue: informational, atmospheric, relational, and more

If you are a creative writer curious about the intersection of theology and writing, longing for some practical tips for craftsmanship, or looking for community, please look out for the next Habit course.

A Question of Authenticity: How Vulnerable Should You Be on the Internet?

This question has been brewing in me for years: how vulnerable should you be on the internet?

I think this question started when I began blog-writing after college. I was inspired by the beautifully-crafted blogs and creative fiction of writers from places like the Rabbit Room or podcasts by artists, entrepreneurs, and other content creators: storytellers who captured the music of their lives in relatable but profound prose. Following their example, I translated my own life into words. I wrote vivid descriptions of scenery and seasonal changes, books I read, conferences I went to, meditations from Scripture, weaving them all into a few themes that culminated at the end of each blog post. My year in Scotland yielded a lot of fruitful experiences I could glamorize: gorgeous hikes in the countryside, fascinating lectures and reading assignments, and plenty of academic research to give credibility and substance to my musings on life, literature, and faith.

The years since returning to America, however, have not been as easy to write about. I’ve gone through a lot of change, including a few moves. Many of the mini-seasons in this long season have not been easy to write about — not for particularly interesting reasons, but because they included plenty of isolation, boredom, and loneliness, which don’t make for great writing material.

For the past few months, reflecting on my original goals and life since graduate school, I’ve been wondering: how much is it healthy, good, or noble to be vulnerable on the internet? This question multiplies into more:

- How do you know when to share a personal story and when to keep it for your inner circle?

- How long should you wait to write about an experience?

- How do you respect others’ privacy when you share stories in which they’ve participated?

- How many details should you share about a painful or difficult experience?

- Should you write about unresolved conflict or past hurts? If so, how?

- How hard should you try to end your personal story, especially a difficult one, on a certain emotional note – especially if you’re not sure that chapter of your life is finished?

Recently, I began pondering the question of Internet/public vulnerability in general after attending a conference in which a successful author, blogger, and podcast guest gave the keynote talk. He shared some deeply personal stories as part of his message: horrifying family tragedies, personal doubt, career struggles, unexpected triumphs, and new directions he’s taken. I’ve heard enough speakers by now to recognize some of the techniques he used, such as careful repetition, including concrete detail, and framing the whole talk with a quest structure. I’ve sat in lectures and talks with speakers who moved the audience to murmurs of awe, even to tears. Unfortunately, this one did not. Something about the speaker’s attitude, the personal details he revealed and concealed, the vaguely spiritual but self-centered ethic he preached, and the crescendo of his talk left me feeling emotionally manipulated — and awkwardly sitting during the applause as many of those around me rose to a standing ovation. I felt that the speaker was using grief and pain from his past to paint himself as both a victim and a victor and tell me how to run my life.

While this speaker was talking to a live audience, not on the Internet, his talk pushed me to a preliminary conclusion. How vulnerable should you be? is a wisdom issue, not a yes/no or fill-in-the-blank question. I walked away convinced that yes, there are good reasons and good ways to do so as well as bad ones. But how do you discern the right reasons and the right ways to share your story?

It’s as difficult a question as the one that haunted me in the post-college years: how do you live a good life? How should an artist use the raw material of her life, especially intimate things like family memories and struggles, in her art? Or should she do so at all?

Vulnerability and Influencer culture

On the internet, on social media, vulnerability is powerful. Someone who can share intimate, specific details of their days, families, work, hobbies, emotions, struggles, trauma, and celebrations can draw a following. I know of influencers who I deeply respect and have taught me wonderful things, but I’m becoming uncomfortable with how vulnerability equals money in the transaction of paid platforms, book deals, and commission sales.

Of course, people who work hard to create beautiful and useful things should be paid for their work. But I am getting concerned about a particular pattern: someone shares intimate details about their life consistently enough that their followers feel like they are personal friends – and, also, students and disciples. An influencer can become a personality who coaches followers on any topic: faith, mental health, life goals, relationship difficulties. One influencer I used to follow on Instagram went from giving life-advice and career coaching to selling a product by commission. She introduced a major world problem and talked extensively about it, then encouraged her followers that that product was a solution.

I know a few influencers who do a great job of cultivating real relationships in the online communities they’ve set up, and encouraging those followers to build real relationships with each other. My concern is when the relationship remains one-sided, digital, and transactional: the influencer offers vulnerable life details, and the follower reciprocates with likes, shares, attention, promotion, and money. Vulnerability sells.

Vulnerability, authenticity, truth: entering other territories

That keynote speech at the conference was just one thing that triggered this question in my mind. Another catalyst was the brief glance I took of a book of publishing advice for nonfiction writers. The book advised writers to be wholly “vulnerable” with their stories: write in blunt detail about humiliations, failures, scars, traumatic experiences, and deepest secrets. The book is a bestseller, and the author is right. Readers love intimate details, especially when they can get them without sharing their own secrets. But that advice makes my introverted self want to head for the hills.

I’m a hypocrite in this area. I love it when other writers share their intimate stories so I can read them from the comfort of anonymity. I crave the juicy details of their romances, either breakups and happy endings; parenting anecdotes; college tales; childhood memories; vacation stories; secrets; and I love not having to share any of mine in return. But vulnerability creates the illusion of friendship and intimacy without the full reality, and I’m afraid it just feeds the loneliness of our culture.

How vulnerable should you be on the internet? After all this thought, I finally looked up the definition. According to Merriam Webster, to be “vulnerable” is to be “capable of being physically or emotionally wounded,” or “open to attack or damage : assailable.” Ouch. But it is true. Sharing childhood memories, family stories, thoughts, and dreams on the Internet does leave you open to attack: mockery, scorn, criticism, and getting cancelled.

So why share your story at all?

I think back to some of the personal essays that have touched me deeply:

- E.B. White’s “Ring of Time” and “Once More to the Lake” from his essay collection — achingly beautiful reflections of memory, time, and immortality, grounded in rich detail

- Lanier Ivester’s “Seeds of Love” — an exquisite mingling of personal loss and eternal hope

- Jennifer Trafton’s “This is For All the Lonely Writers” — a very relatable, exquisitely crafted meditation on loneliness, creativity, and community

- Lancia Smith’s “Yes, Virginia, I Still Believe in Jolly Old Santa Claus” — a thought-provoking, joyfully reverent study of how the Christmas icon figures the tender love of God

In A Discovery of Poetry, Frances Mayes begins by exploring the purpose and meaning of poetry. “All these images [from poems] form a quick glimpse of how those mysterious others behind the glass live their lives. Poems give you the lives of others and then circle in on your own inner world . . . Like play, poetry lets us enter other territories” (xiii-xv, emphasis mine).

Well-written creative nonfiction and personal storytelling does the same, as do fictional stories. They give us a glimpse of another’s life, let us enter their territory. Done well, it’s invitational, relational, encouraging, challenging, comforting, and thought-provoking.

How vulnerable should you be on the internet? How vulnerable should you be in any form of writing? I think now of David, Asaph, Moses, and others pouring out their hearts in the Psalms; Nehemiah penning his cry to the Lord when he heard Jerusalem was in ruins; Paul writing of his past sins and current persecutions to the beloved members of the early church. Yes, for the right reasons and in the right way, opening yourself up to be wounded is a gift to your audience. Not to build a following of people who feed on your life and your advice, but to welcome them into following the Lord, the One of all creation who has the right and the goodness to influence us ultimately.

Some tentative personal resolutions

Public vulnerability is a wisdom issue, something that requires individual reflection and discernment. Done well, it’s a beautiful gift to readers; done poorly, and you really have opened yourself up to be wounded or to wound your readers. As I ponder this, here are a couple of principles I’m forming for my own writing:

- Let Scripture guide you into making God the center. Use my writing to recognize the work of the Lord – not by slapping a Bible verse or pious-sounding conclusion onto every piece, but trusting that if I pay attention to detail, take the time to ponder an experience, and pray over it, I will find its intersection with eternal truth. I’ve seen this modeled brilliantly by the writers at The Cultivating Project, who weave Biblical insights, hymns, and other art into personal stories. A good artist can turn the telos or purpose of a piece into hope-through-lament, courage-through-darkness, joy-through-sorrow, and faith-through suffering without minimizing how hard life is.

- Tell family and friends first. This is an old rule I made for myself, and I think I’ve managed to follow it. If I have exciting news in particular, I try to let my closest circles know first, and they get the real scoop on the most interesting details.

- If it’s a hard subject, pray and wait before sharing. I don’t think I need a waiting period to share a fun hiking story or list of good books I’ve read recently, but if I choose to share something painful or complicated, I want to make sure I have a good reason for doing so.

- Err on the side of others’ privacy. I never want to burn a relationship by turning a painful or private subject into a piece of content. Any money I might get from a commissioned piece, any number of likes, follows, or shares, is not worth hurting someone I love.

What do you think about vulnerability on the Internet? Where have you seen it modeled well or poorly? And what are some of your favorite examples of personal stories told well?